And their investigations indicate that size matters.

Because they’ve found evidence that when this microscopic part of the cell is relatively compact and small, your odds of living to a ripe old age take a leap. But if it gets bigger, that can signal a greater risk of dying young.

Important news for all of us.

The Cell’s Mini Protein Factory

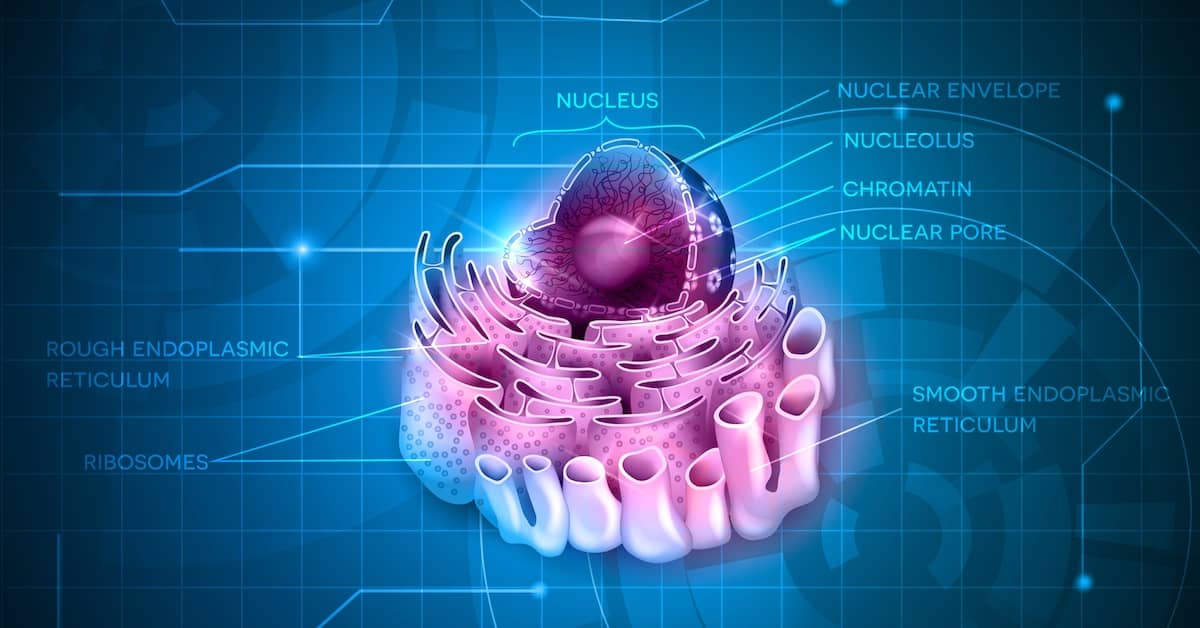

The structure that has aging experts excited is called the nucleolus. It‘s so small, it’s contained within each cell’s nucleus, and it’s kind of like a nucleus within a nucleus. Each of our cells has one of these and so do the cells of all plants and animals.The job of the nucleolus has long been understood to be the production of ribosomes – small assemblies of molecules that put together the proteins a cell needs to survive. Consequently, biologists have referred to the nucleolus as a “ribosome factory.” Producing these proteins consumes about 80 percent of the energy a cell expends.

In their tests, though, investigators have now discovered that the nucleolus is more than just a passive constructor of ribosomes. “Our work and other people's work shows that the nucleolus plays many different roles, including lifespan control,” says researcher Adam Antebi, director of the Max Planck Institute for the Biology of Aging in Germany.

In many of the studies of how we and other living things age, scientists have examined the process in worms, yeast, fruit flies and rodents as well as in humans. In these tests, exercise and dietary restriction (eating less food and consuming fewer calories) have proven to be two of the most effective ways to slow aging.

Bigger is Better, If You Want to Live a Long Time

When Dr. Antebi and other researchers have looked at events in the cell that moderate aging, they have found that the chemical pathways that go into action to prolong life affect the size of the nucleolus.1 The result: When the nucleoli are enlarged, the life span shortens. But when the nucleoli shrink, life expectancy stretches out longer.The key to making the nucleolus smaller seems to be increasing the actions of a gene known as NCL-1. When we restrict our diet or consistently exercise, for example, NCL-1 goes to work, causing the nucleolus to get smaller and cut back on making ribosomes.

In contrast, studies show that in the cells of people suffering from life-shortening illnesses like cancer or progeria (a genetic defect that causes rapid aging) the nucleolus is always enlarged.

Researchers believe the link between a reduction in nucleolus size and longevity is probably related to creating a healthy homeostasis in cells – enabling cells to create new proteins while repairing or recycling older ones at a healthy rate and in life-prolonging proportion.

The studies also show that organs in the body that age slowly have smaller nucleoli than organs where aging proceeds more quickly. Lab tests, for instance, show that this may account for why neurons, muscle cells and skin cells show differences in their capacity with the passing years. While skin and muscle cells with larger nucleoli age at a more rapid pace, for people (and other organisms), neurons, having smaller nucleoli, don’t generally deteriorate at the same rate.2 That could possibly explain why a very old person on his or her deathbed may have wrinkled, old-looking skin and wasted muscles but can still have a brain that understands everything that is going on. Or, even if the brain has been ravaged by dementia, an organ like the heart may keep on functioning. Not every part of the body ages and breaks down at the same pace.

Researchers hope that their studies of the nucleolus can reveal more insights into methods for slowing down the aging process. And this tiny but very busy part of the cell may provide an easy way to measure life expectancy.

“We’ve spent lots of money on trying to find biomarkers of longevity or aging, and maybe it’s just sitting under the microscope for us to see,” says Dr. Antebi.3